David González writes on Angel Franco.

David González: Angel Franco and I have been friends since 1979, when I was a rookie photographer working for En Foco in the Bronx and he was a shooter with many magazine assignments. We stayed in touch over the years, and in 1989—after I had put down my cameras and become a reporter—we reconnected when he was at the Times. He had suggested we work together, and having soured on the over-edited group journalism at Newsweek, where I was the Deputy New York Bureau Chief, his idea sounds good. At the time, the newspaper was ramping up its local coverage, and someone like me—a bilingual native New Yorker—was someone who could help. Introductions were made, and an offer was extended.

I jumped at it.

From my earliest days at the Times, Franco and I have collaborated as often as possible on a wide range of stories. If anything, our partnership rests on a desire to document the lives and neighborhoods of Latino New Yorkers, especially Puerto Ricans. At the same time, we have been passionate about chronicling the margins of the city seeing how the less fortunate have been faring in this land of plenty.

Some of that is based on a common ground we share as Nuyoricans who grew up in blue-collar communities in the 1960s. We see this city in a very different manner—and hear it in a different language—than a lot of reporters and photographers who parachute in and think they have “discovered” us. We see it as insiders, with all the nuanced grays that exist between black and white.

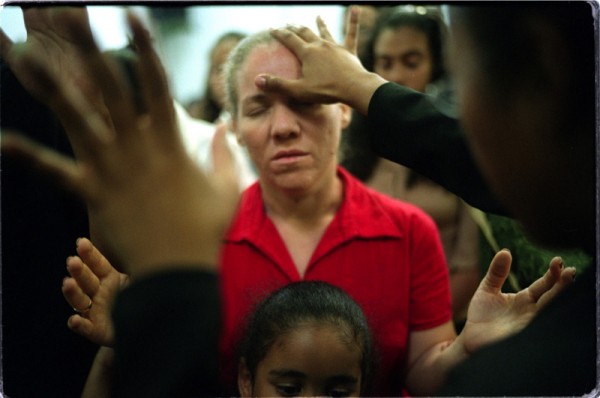

The Storefront project is in many ways the culmination of our long-standing partnership. We saw it as a way to explore an omnipresent yet misunderstood feature of the urban landscape. The Pentecostales—Los Aleluyas—have been caricatured as some sort of fringe group. But in reality—and as my work overseas showed me—they are a rapidly-growing phenomenon. They have helped people adjust in societies where there has been rapid change and social dislocation. They have played a similar role in New York, reaching out to the newcomer and the dispossessed, offering them a spiritual and cultural home.

The idea was to immerse ourselves in this world, and in doing so illustrate how a global trend can be found in a tiny storefront church in Harlem. The local is informed by the global.

I think the years I spent as a photographer made me sensitive to the relationship between reporter and photographer. It gives Franco and me a common visual language through which we communicate. Somebody once remarked that we work so well together that we do not have to speak anymore. Nonsense. Our communication is based on talking A LOT about the stories we are doing, discussing the interviews, the pictures and the scenes were are reporting on. To suggest otherwise is to ignore the hard work that both of us bring to this.

Franco’s eye is tuned into my reporting and vice versa. The result is collaboration where the words and images complement each other. There were times during the reporting where he saw something and discreetly tipped me off, so I could pursue it later. I cannot tell you how many times he has done this (and how some foolish reporters don’t pay attention when he tries to hip them to something! You ignore him at your own risk.)

I know that Angel’s personality put a lot of people at ease in the congregation—something that happens often. Also, the fact that we were two Spanish-speaking reporters gave us a cultural common ground with the subjects that made them comfortable around us.

This project represents the fullest realization of our collaboration, but there have been others. In 2003, we spent a month reporting on how HIV/AIDS was affecting the Dominican Republic. We went throughout the whole island, reporting in bars, clinics and bateyes. We accompanied sex workers as they showed bar patrons how a woman could put on a condom with her mouth (the bar patrons almost rioted). We crouched beside a dying plantation worker who still denied he had AIDS. And a doctor was so comfortable around us that she invited us to her office when she was breaking the news to a patient that she was HIV-positive.

In a lot of this, we discuss the story and the reporting as we go along. But the great thing about Franco is that he trusts in the moment. He has taught me to relax and be open to those serendipitous moments when the reporting goes to another level.

Working with Franco has made me realize how serendipity can be a reporter’s best friend. Too often, especially among less-experienced reporters, there can be a tendency to go looking for what you expect, rush through the interview and head back to the newsroom to write it up. But in doing so, we blind ourselves to those unguarded moments that are hidden in plain sight.

When we begin reporting a story, we just look around and talk about the scene we are seeing. Often, we don’t start interviewing or shooting until we have a feel for the place and perhaps are intrigued by someone or some scene or detail in particular.

Sometimes it happens when someone we have been interviewing/photographing feels so at ease with us that they invite us to get a closer look at their world (like when the Dominican doctor asked if we wanted to sit in on a consult when she broke bad news to a patient).

Other times it has been because we stuck around after we have “officially” stopped reporting, more or less tumbling onto something. Years ago, we had moved in with a community of Franciscan Friars in the South Bronx for a week. By Sunday, we had more than enough for our series. But we accompanied one friar to Sunday Mass. Afterwards, Franco noticed a woman sobbing on the steps of the church. She had gone there, she said, because she had heard the friar looked like her son, who had been murdered a few years earlier.

The moment—the friar gently consoling the sobbing woman—made for a great picture and provided our series with the perfect—and unexpected—kicker.

Serendipity is your friend. Now, that doesn’t mean we do not prepare, research or think about what we are doing. We do—obsessively, in fact. And by preparing ourselves so, we are positioned to recognize the gifts that serendipity puts in our paths.

And we wind up looking like geniuses—lucky ones.

—Written by David González (based on an interview by Adriana Teresa)

Captions

Top: Congregants at the Pentecostal Church Ark of Salvation for the New Millennium lay their hands in blessing on a visitor to their storefront church. Members of this church in West Harlem believe the Holy Spirit has infused them with gifts that allow them to prophesy, speak in tongues and lay healing hands. (Photo by Angel Franco/The New York Times)

Bottom: Pistoleros, Mott Haven, August 10, 1979 (Photo by David González)

—

Originally published on the New York Photo Festival blog