Interview by Adriana Teresa Letorney

Larry Fink, born in 1941, started taking photographs as an adolescent. His work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, among others, and he was the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976. His books include “Social Graces” (1984, reissued 2001), “Boxing” (1997), “Runway” (2000) and “The Vanities: Hollywood Parties 2000–2009,” which will be published this year by Schirmer/Mosel. He is a professor of photography at Bard College. This conversation, with Adriana Teresa, the co-founder of FotoVisura and the publisher of Visura Magazine, has been edited and condensed.

Q. When did you start to photograph?

A. At the age of 12. I was such an angry, raging, roiling kid. By the time I was 14, I was seriously obsessed by its practice. Then I won a contest. I won a Kodak Brownie Hawkeye camera — yeah! — for a picture I did of a guy descending a staircase with a lot of different textures in it. I was already looking at Cartier-Bresson because my daddy brought me home the books “The Decisive Moment” and “The Europeans.” I was invigorated by the cultural life that my family gave me, which was full of the American realist artists and jazz, not to mention classical symphonies. The deeper expressions of life, as well as very active leftist social concerns, were paramount in my family. All of those things led me into photographing in many different ways and many different directions.

Q. Is your work a reflection of your life?

A. Yeah, in some fashion or other. I didn’t mean “Social Graces” as a Marxist statement, even though I am a Marxist or, at least, I was a Marxist before the world became an impossible place to predict.

My mother was a Marxist and an organizer, but she was an elegant gal. She liked to wear minks and furs, and vacation in Florida. And she quit the party because the party was rigid and puritanical. She said: “It is ridiculous. Why sublimate your need for elegance and joy and class and style and fun — for the cause? The cause will be there forever, perhaps. I won’t. I am going to live my life as fully as possible.”

That set of contradictions embellished my politics and aesthetics. The work was meant to be political, not polemical. It turned out to be not necessarily kind, but certainly honest. And not cruel. Ever. I never could be cruel. I really do embrace — or try to embrace — the souls of all people, regardless of their conditions.

Q. How did “Boxing” come together?

A. I used to listen to the Friday night fights. We were people of the left. Boxing was a symbolic sport for people who were underdogs to come up and prove themselves triumphant and powerful. When I got older, I would watch a boxing match on television and find my adrenaline building to a point where my heart palpitations would start and I would have to turn away from the screen. I guess the latent aggression was flamed by the stimulus. So I didn’t think about boxing.

“In the field of boxing, you have unbelievable purity of intention and innocence, and unbelievable greed, evil and belligerence, all sitting in the same stew pot. It’s a spicy stew. I like spicy stew.”

Kathleen Klech, an important picture editor, was working for Manhattan Inc. She had studied “Social Graces” and wondered if I would be able to work. I was willing to work. As a matter a fact, I was desperate to work. So she gave me an assignment to photograph Jimmy Jacobs, the manager of Mike Tyson. I went to the Catskills and found Jimmy and Mike and photographed around. While I was in the ring and in the gym, I found myself having a great, oddly powerful feeling of total calm and peace, and a sense that I should be there. So, I stayed. Not to photograph Tyson and only Tyson — like others did — but basically to just hang out. I mostly did my work in Philadelphia, which is a great boxing town. Champions were not my interest. My interest was the harmony between boxers. In the field of boxing, you have unbelievable purity of intention and innocence, and unbelievable greed, evil and belligerence, all sitting in the same stew pot. It’s a spicy stew. I like spicy stew.

Q. How would you describe “Runway”?

A. It was an extension of my interest in documenting the rich and their habits, which began in “Social Graces.” Because of my reputation as an artist and my critical point of view, some people within the world of fashion wanted me to contribute to their magazines. Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W magazine, was one of the first who gave me access to the fabled world of fashion.

I was critical — not hypercritical, but critical with the system — and at the same time, I was becoming part of the system. One of the contradictions of my life, a deep one, is that duality. Then lo and behold, I became a contributor under contract to Vanity Fair for 10 productive years.

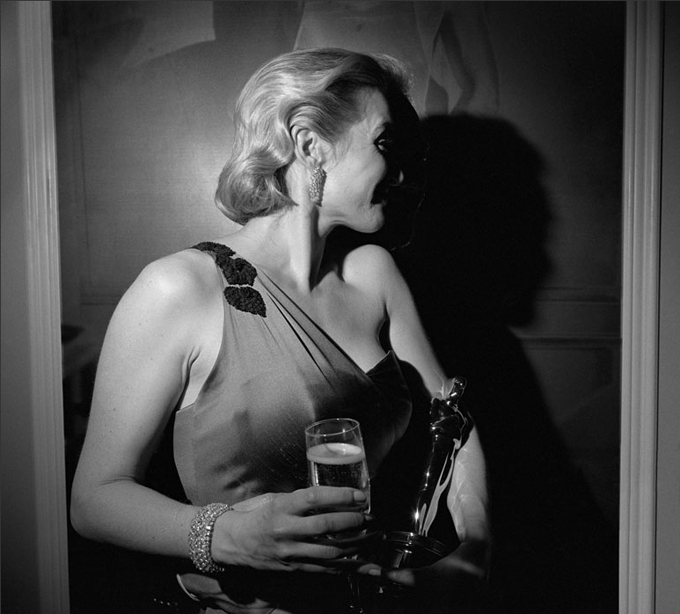

Q. What is “The Vanities” about?

A. “The Vanities: Hollywood Parties 2000-2009,” accompanying a show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art [“Larry Fink: Hollywood, 2000-2009“] is essentially about the parties that I was privileged to photograph for Vanity Fair.

Q. What made you want to distort beautiful rich people in parties or at the Oscars?

A. I don’t distort. I comment honestly and make pictures of my perceptions. The celebrity is but a person to me. I see them within the primary moment. I try not to have previous assumptions. Each moment is the only moment that we have. We have to enter it without prejudice and with the thought that it may be the last one. The photograph is an attempt to give the perception of the moment some relationship to immortality.

Q. Besides photography, you are knowledgeable in music, literature, painting and construction.

A. My life is my art, and photography is part of it. The art of my life is a very broad life, which is to say that I kiss the soft wind when it goes by, and I embrace the hard wind so it doesn’t flee. I am wet and I am dry. I laugh and I cry. I live to do or die.

I play piano for probably half an hour to an hour a day — jazz. I started that at the same time as I started photography. Music feeds the deepest core of my life. I live on a farm with my wife, Martha Posner, a sculptor. We work the farm in a productive way. We have probably 75 animals of every kind and we take care of them. Not to mention gardens of all orders. This year, the tomatoes were wonderful.

“I don’t distort. I comment honestly and make pictures of my perceptions.”

—Larry Fink

It has been a necessity and a pleasure to have to learn to work with my hands. I used to live in a loft in New York, back in the day, when they were illegal. This was before there was lots of money in the art world, so I did all the work myself: the electricity, plumbing and carpentry. I built up this farm from those skills, and became more advanced by doing so. I even went so far as to completely reconstruct a 1941 Oliver bulldozer. The whole damn thing! Took me three months. My life is — within reason — that of some kind of Renaissance man, without being too puffed up with that title and meaning; but just the idea of enjoying and doing so many things. I am an inexact botanist. I have a greenhouse full of plants.

Q. What does your work say about you?

A. It’s about empathy. But the necessary methodology is conventionally in-your-face. Not like other practitioners, who are in your face for the sake of being in your face, I am in your face because I want to be your face. I like to say that if I was not a photographer, I would be in jail. I want to touch everything. My life is profoundly physical. Photography for me is the transformation of desire.

Q. What is the most difficult thing for you about your photography?

A. I don’t like to hurt people. I go after something and I start pointing the camera at somebody, looking for those hard, edgy things I know I am going to find. My pictures will be out of bounds in terms of the convention of how this person wants to be represented. It gives me pause. I don’t feel I have the right to do that. But I do it nevertheless. After all, a picture is not a murder. It is simply a moment which suggests so many things. Now, when I photograph very invasively, I try to make jokes and make people happy. I am not interested at all in making them upset. I try to make people feel comfortable.

“Photography for me is the transformation of desire.”

—Larry Fink

Q. What in you is in every picture?

A. People who look at my work often think of one of my favorite painters, Caravaggio. In my life, I’ve been not quite as extreme as he was, since I haven’t murdered anybody. But I have been into all kinds of mischief. I have been in jail. I’ve stolen things: cars, money, cologne. I’ve been solid as well as liquid, perverse as well as pure. I have been mean. In my younger days, I’ve been really mean. My mother taught me; she was mean, among many other things. I’ve been blindly belligerent. I’ve also been like my father, who was kind, loving and intelligent. So, I have done a lot of things in this life that allow me a breadth of experience. I’ve done things I am ashamed of that I can still say are mine. I wouldn’t hide them. I wouldn’t gloat about them, either. All of these acts add to my work insofar as they give me a multilevel sense of experience, which comes forth in the core of the work.

Q. How would you describe the relationship between the images and you?

A. I do not know if I can, actually. I don’t know if I work with that kind of psychological precision, back and forth between imagery.

I was severely analytical when I was young, like when I was doing “Social Graces.” I was a good-looking kid. My mother was very vain, competitive and judgmental, and I took on the same characteristics as a younger person. I used to judge people out of the hardness of my heart. So, I went into these very voluptuous and elegant bourgeois circumstances, and I would judge these people as if they were the enemy. I believed the work to be analytical, in a political fashion.

“I went into these very voluptuous and elegant bourgeois circumstances, and I would judge these people as if they were the enemy.”

—Larry Fink

When age had given me entry into life’s harder organic experiences — my back, my heart, my prostate, my hip — I started to look at my own face in the mirror and see the results of pain. I would see that many of the judgments I had made in the early days, based on an ideal sense of a physical equilibrium, were absolutely and horrendously bigoted. I was not at all sensitive to either the inner or external trappings of what it means to just be alive and all its various, vulnerable complexities.

In the early days, I used to think I could take one picture, and if it were successful, it would epitomize that human being. Now, I think that is an absurd notion because I see that all people are 360 degrees around. Stories are being told and retold each moment. Truths are being discovered and rediscovered. Being alive is sometimes soft, sometimes hard, but always complex. Life has become more worthwhile, even though the political and moral struggles that I thought might have been mine — or my generation’s — to solve have been dynamic failures. Nothing has been solved. This fact could bring depression and disillusionment. Long ago, though, I left my illusions behind. Now, I simply proceed toward making each day worthy.

Q. What does everything that you have photographed mean to you today?

A. That I live with passion and that I care.

The moment that we have is the only moment we will ever have, insofar as it is fleeting. Every breath counts. So does every moment and perception. It’s a way to be alive. I am involved with the idea of reaching deeply into the pulsing matter of what it means to be alive and being vulnerable and seeing if I can cast an emotional legacy about being human.

. . .

Originally published in The New York Times Lens Blog, January 6, 2011